Geology of the coal measures of South Yorkshire

Coal is close to the surface around here, some stream beds are made of coal in the undulating countryside (for example between Kiveton and Harthill), and in the 20th century strip mining has extracted millions of tons of near surface coal at Treeton/Orgreave. For example, a strike call banner from 1948 claimed that near to Norwood there was a coal seam of 200 acres of good quality coal, 4ft. 6ins. thick. There were 4 deep mining pits in the villages area that closed in the early to mid 1990s i.e. Dinnington, Kiveton, Shireoaks and Thurcroft, (and dozens of others of the Yorks and Notts coalfields – see List of pits 1987). Maltby pit remains though, and employs about 500 to produce about 1m tonnes of coal per year.

The Barnsley seam (also called the Top Hard seam) covers an area much greater than that of this website: it’s mined in the Selby coal mines some 50 miles to the north. It’s up to 3m thick and dips from west to east so that locally its at about 400m depth, but at Scaftworth (SK 6718 9228) it is 821m deep, e.g. at Thurcoft it is at 745m below the surface, but at Markham Main it is at 680m. This is partly explained by the fact that Thurcroft is 117m above sea level whereas Markham is just 20m above sea level on the plain east of Doncaster (so if global warming melts the ice caps and raises sea levels then it could be Donny by the Sea in a couple of centuries time!). It is high quality coal that is excellent for boilers, whether they be in the firebox of a Victorian steam train, or a 21st century power stations’ steam turbine (such as Drax on the Humber). Also, underfoot in this area is the High Hazel seam at about 270m from the surface. High Hazel was a very good quality house coal back in the days when smokey coal could be burnt in a house fireplace, i.e up until about 1990. At a depth of about 600 metres (in the Rotherham area) is the approx 1m thick Thorncliffe seam, apparently good for coke only.

Kiveton pit was about 90m above sea level, and the depth of measures is given at Kiveton,if only because it was one of the oldest and deepest mines, and therefore has a good set of data available to me from borings and geological surveys. Some collieries were very shallow, e.g. Waleswood which was worked between 1902 and 1926 worked the High Hazels, Flockton, and Thorncliffe seams down to a depth of 200m. The full list of seams, starting from the Silkstone nearest the surface (and therefore laid down last). Generally,the best coal is the deepest – see the Coal Grades link left.

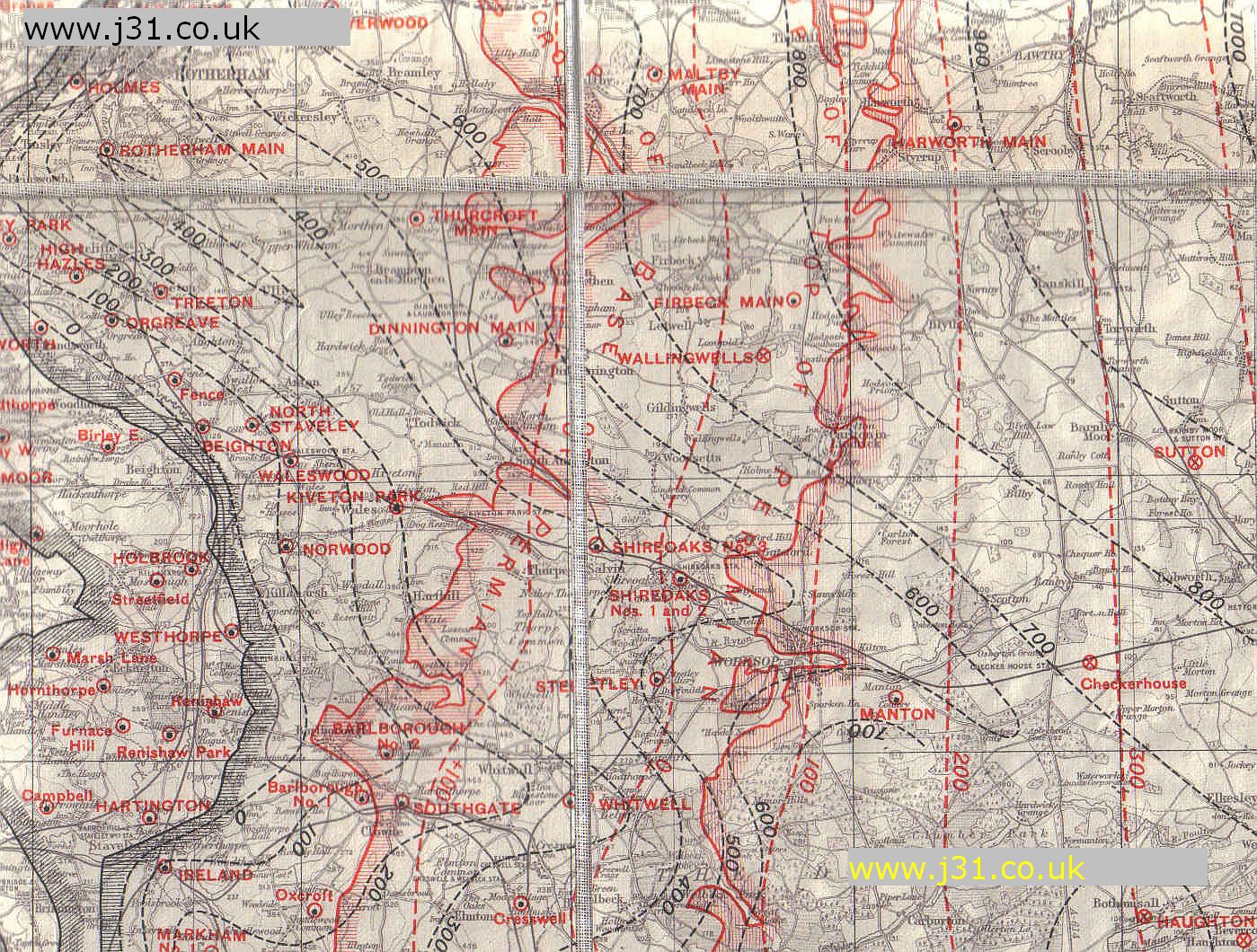

The contour map below shows where the Barsley seam breaks the surface. The other broken black contour lines indicate where the Barnsley seam is 100, 200, 300 yards etc. below the surface. The red contour lines indicate the top and bottom of the Permian rocks (about 250 – 300 million years old) that are younger than the carboniferous coal measures (circa 360 to 299 million year old).

Location of pits in 1926, and depth of Barnsley/Top Hard seam (dashed black contour lines in yards below the surface).

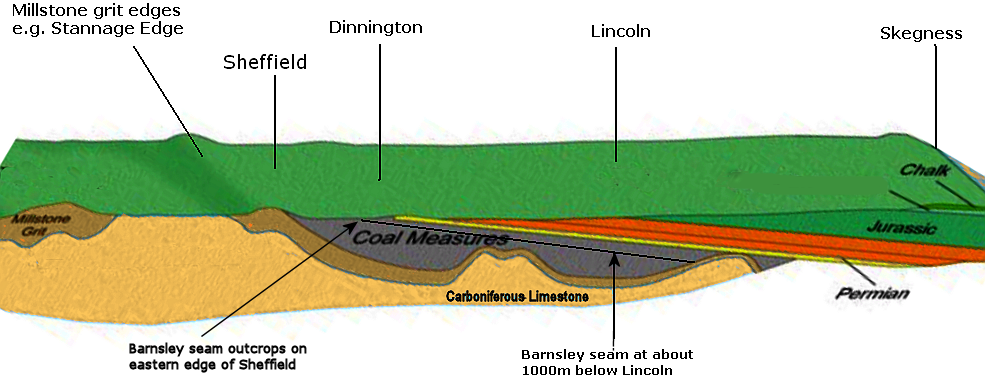

The map covers about 30 miles/ west to east, heading from the foothills of the Pennines out to the plain of Lincolnshire (via Worksop/Retford in Nottinghamshire). The Barnsley seam is at the surface in the Sheffield area, but by the time it reaches Lincoln, 40 miles to the east, it is about 0.5 mile/1000 metres below the surface. It’s as though the once horizontal strata were tilted at a 1 in 20 (5%) slope, and then the highest bits sliced off like cleaving the top from a boiled egg.

This picture illustrates the tilt of the coal measures:

The deepest coal mines in the world are up to 1500 metres deep and are at 50C temperature (possibly Westphalia Germany), deeper than the height of Ben Nevis (1440m). The deepest mine in the UK in 2007 is possibly Maltby collieries’ number 3 shaft at 991m (the Parkgate seam I think).

The deepest ever coal mine may have been Springhill Mine, Nova Scotia, Canada, at circa 2000m, but it closed in 1958 as ‘it was too dangerous to continue digging.’

generally speaking, in a given area the deeper the coal seam the higher its rank or quality (see Coal types left).

The deepest mine in the world is the Western Deep Level gold mine in South Africa, with shafts up to 3900m deep – the temperatures are circa 60c, over the limit of human endurance. Mining activities there induce seismic activity at up to magnitude 4 where they remove 1 tonne of ore to extract 12 grammes of gold (less than a third of a Troy ounce). To make it endurabe at such depths the mines aren’t just ventilated, they are air conditioned. Such expenditure may be justifiabe for gold at over $1500 a troy ounce, but not for coal at under $0.01 an ounce! (2011 ballpark figures)

The table below is an estimate of the depths of the seams below the old Kiveton colliery. I got the data from sections of strata tables from 1927 and 1950, and not all seams were explicitly named. Moreover, at Kiveton the strata dip by a gradient of 4.5%, or 45m per kilometre as the Carboniferous coal measures dive below the surface towards the North Sea over 100 km distant.

The names of the seams and their location with respect to each other remains the same throughout most of the Yorkshire and Derbyshire coalfieds. Bearing in mind that the Barnsley/Top Hard seam outcrops around Beighton, all 11 seams of coal that were once above it on the Pennine side of Sheffield have been weathered away, or scraped off by successive ice sheets.

From the surface to the bottom of the deepest borehole around Kiveton (at around 1km below the surface) there were about 350 different layers of rock identified, including the coal seams in the table below.

| Coal Seam | Description | Approx depth (yards/meters) at Kiveton |

| Shafton Seam | Industrial & Brick Making Coal. Also known as the Billingley, Heringthorpe , or Nostell Seam | 50/45 |

| Bagshaw’s Coal | Possibly also called Sharlston Top, Low and Yard coal, Holywell Wood or Houghton coal. | 77/70 |

| Swinton Pottery Seam | A poor quality coal, used for brick making. Also called Wheatworth or C astleford 4 foot coal , or Bateson’s Bed . | 88/80 |

| Newhill or Steam Coal Seam | A household coal. | 181/165 |

| Aston Common Seam | A household coal also used for coke making. Also called Meltonfield , Wath Wood , Wakefield Muck , or Clowne coal. | 209/190 |

| Fox Earth Coal | Designated Coal and Bat (inferior) | 240/218 |

| Sough Coal. | The seam was rarely worked and was often split by a dirt parting. Also called Two Foot Seam , Royston , Cat Coal , or Halfyard Seam . | 254/231 |

| Furnace Coal | This seam is called the Winter seam north of Barnsley and the Abdy seam south of the town. A household coal not mined extensively because the roof of the seam was often a shaly mudstone which made mining it difficult.Also called Scale coal . | 265/241 |

| The Top and Low Beamshaw Seams | These seams produce a good household coal with a low sulphur content but are often split by shales and in places they are separated by 10m of dirt.Also called Stanley Main coal. | 283/257 |

| Kents Thin Seam | A good household coal. | 287/261 |

| High Hazels Seam | A good household coal, often mined. AKA Kents Thick , Mapplewell . The seam is split by a thin dirt parting known locally as Bannocking dirt. | 313/284 |

| Barnsley Rider Seam | A thin band of coal 15 to 30m above the main Barnsley Seam. Poor quality, little coal mixed with lots of rock and dirt. | 384/349 |

| Top Hards seam AKA the Barnsley Seam | This was the most important seam in the coal field and 50% of the coalfields output came from this seam. Up to 3m thick but around 1.2m in Kiveton. According to the History of Kiveton Pit article it was exhaused in Kiveton circa 1970 (unverified).The seams consistency varied from top to bottom. The upper portion was a bright soft coal, the middle portion a hard dull coal known as the “hards” and the lower portion another band of bright soft coal. The hards were used in locomotives and steam ships. The soft coals were mixed with other coals for coke making. | 401/365 |

| Dunsil Seam | Between the Swallow Wood seam and the Barnsley Seam numerous thin seams of coal are found, To the south and east of Barnsley the coalesce to form the Dunsil seam a poor quality coal with a high ash and sulphur content. | 414/376 |

| Swallow Wood, | The quality of this coal seam varied but it generally provided a household and gas coal and was some times used as second class steam coal.Also called Netherton or Top Haigh Moor Seam. | 455/414 |

| Eckington Deep Softs | A household coal that forms a thin seam with shale partings. Often not worked.May be called the Lidgett Seam. The UK Coal Thoresby colliery in Nottinghamshire mines the Deep Soft seam at 830 metres (913 yards), possibly this seam. | 591/537 |

| Joan Seam | A thin seam of coal not generally worked.Also called Mitchell or Parson’s coal. | 600/545 |

| The Flockton Seams | There are two seams of Flockton coal, the Flockton Thin which is the lowest and is generally too thin to work and the Flockton Thick which lies above it. A good household and coking coal.Also called Heward or Adwalton Black Bed coal. | 608/553 |

| Fenton Seam | A Gas & Coking Coal. The seam is often split by a “Spavins” thin layers of earthy clay with rootlets or larger partings of shale. This often results in two distinct seams called High & Low Fenton | 615/562 |

| Parkgate Seam (may include the two seams below) | A good quality industrial coal used for gas manufacture that after the Barnsley seam is the most important in the South Yorkshire Coalfield. A three part seam consisting of Tops, Bottoms (used for gas manufacture). and Middle Hards (a good steam generating coal). | 632 – 646/575 – 587 |

| Thorncliffe Thin Seam | A good quality low ash coal that was used for steam raising, gas and house coal and the smalls were used for coke manufacture. Often split by dirt partings. | 632/575 |

| Swilley or New Hards Seam | Coal suitable gas and coke production. The seam consists of “tops” and the “bottoms” split by a dirt parting. The seam is very variable and seen little south of Barnsley i.e. in the Rotherham area ofJ31. | 640/582 |

| Thorcliffe Coal | Coal suitable for household and industrial use. Silkstone Fourfoot or Wheatley Lime Seam | 669/608 |

| Silkstone Seam | A high quality, low sulphur coal used for coke manufacture and as a manufacturing and household coal. | 732/665 |

| Whinmoor | Aka Shirtcliffe or Beeston coal. | 739/672 |

| Grenoside Sandstone | Aks Crow coal. | 743/675 |

| Black Bed coal. | possibly not reached at Kiveton | |

| Better Bed coal | possibly not reached at Kiveton | |

| Ganister | Aka Halifax Hard Bed coal | possibly not reached at Kiveton |

| Clay Coal | Aka Middle Band coal. | possibly not reached at Kiveton |

| Halifax Soft Bed Coal | Aka Coking coal. | possibly not reached at Kiveton |

| Base of lower Coal Measures | 350 million year old rock. Below this is Devonian rock, 1 kilometre below Kiveton.. | 920/836 |

In the Rother Valley area the most important seams were the Silkstone , Parkgate , Swallow Wood , Barnsley / TopHard and High Hazels seams. In general the upper seams like High Hazels are high oxygen readily burning coals, whereas the lower seams and low oxygen coal that can be made into coke (smoke free fuel).

Figures for the deepest section of strata hereabouts that I could find come from Scaftworth Number 2 Oil Borehole, by British Petroleum in 1982, about 10 miles NNW of Worksop, not too far from Doncaster/Robin Hood airport.

| Coal seam | Description | Approx depth (Metres) |

| Sherwood Sandstone | Eroded away at Kiveton and missing. | 194 |

| Permian Rocks | ditto | 338 |

| Brierly Coal? | ditto? | 382 |

| Barnsley seam? | The ‘Main’ seam in these coalfields. About 365m at Kiveton | 821 |

| Top Silkstone Coal | about 660m at Kiveton? | 1086 |

| Top Beeston Coal | about 672m at kiveton? | 1124 |

| Millstone Grit | Outcrops just west of Sheffield to form the famous rock climbing cliffs of Frogatt Edge, Milllstone Edge, Curber, etc. | 1468 |

| Carboniferous Limestone | xx | 2326 |

Incidentally, it has been estimated that in the swampy river deltas from which the coal came it took about 7000 years to lay down 1 metre of coal. The rock between the coal (e.g. from silting up lakes) could have taken as little as 5 years per metre. So 3 the metres maximum thickness of the Barnsley seam could have been about 21,000 years in the making – the blink of an eye in geological time.

Deep Time: When were the coal measures created?

All of the above were laid down in what are known as the coal measures during the Upper Carboniferous period of the Paleozoic era, a period of geological time from 360 to 299 million years ago. So named because of the global occurrence of coal and limestone (calcium carbonate or CaCO3) that was formed during this time. The bulk of coal deposits in the UK occur in Carboniferous strata. This area was dominated by giant tropical swamps of the club moss trees whose fossilised remains would one day be excavated and burnt as coal (releasing billions of tonnes of CO2 in the process). Flowering plants, such as deciduous trees and flowers, had yet to evolve to dominate the plant world.

The map of the world looked very different then: There was no Europe or Australia, no North America or Asia, there was a supercontinent that stretched from pole to pole called Pangaea comprising all the continental tectonic plates in one huge land mass, and one staggeringly huge ocean over the rest of the globe.

To give you an idea of how long ago this was, at this time there was a common ancestor that we share withwith 4,600 mammals species, 9,600 bird species, and 7,770 reptiles. Tyranosaurus Rex and its Cretaceous dinosaur contemparies lay 200 million years in the future (the Jurassic period was 100 million years away) and that common ancestor was your 170 millionth great grand parent!

Time is an abyss, and on this scale the lifetime of a human is like that of a mayfly. One of the greatest evolutionary advances was that the Carboniferous amphibeans (think primitive fish with legs) developed amniote eggs. The amniote egg allowed our ancestors to reproduce on land by preventing the drying-out of the embryo. The placenta that you were gestated in, and born from, is a modified evolutionary adaptation from the age of coal.

The New Scientist reported an interesting hypothesis as to why the carboniferous ended: It could have been stopped by the evolution of fungi that can eat the woody parts of the ferns when they died. Up till 300 million years ago the giant ferns would have rotted only slowly, or not at all.

There are also limestone quarries, e.g. near to Anston. Some 500,000 tons of the limestone laid down from the shells of marine animals would, 300 million years later (in 1840) be quarried in Anston and shipped via the Chesterfield canal and sea to become the Palace of Westminster aka the Houses of Parliament.